Written by: Monique Oude Luttikhuis

Published: 6-12-2024

For the past twelve years I have been working as a translator and editor of medical and scientific content. Some of the work involved preparing research manuscripts for submission to a scientific journal with the aim of publication. As a former biomedical researcher, that really caught my interest and I decided that I wish to focus more on this type of editing.

With that goal in mind, and to get some more formal training, I took the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) courses ‘Copyediting 2: Headway’ and the ‘Non-Fiction Developmental Editing’. But I knew of one other training course I thought would be a good addition and that was the European Association of Science Editors (EASE) School for Manuscript Editors and Academic Authors. I had to wait quite a few months since the course doesn’t run often. In fact, this was only the second time it ran. Therefore, I was rather excited to register and do it last September – it was a good way to get back to work after the summer holidays.

The EASE training course

This course was ‘designed to help researchers, academics, technical writers and copy editors who edit technical documents to make them more acceptable to journal editors and publishers, less likely to be desk-rejected, and once accepted, be published ahead of other manuscripts’. The training was held over the course of four weeks. Each three-hour session addressed two topics that covered the publication process, presentation of the manuscript and data, and effective writing skills.

The course was presented by Yateendra Joshi, a copyeditor and trainer with over 30 years’ experience. Two of the topics were presented by guest speakers who shared their in-depth knowledge. The 33 attendees came from all over the world, from four continents to be precise, and had various backgrounds: manuscript editors, authors, researchers, author editors, journal office staff, copyeditors and proofreaders.

What I learnt

1. What are the steps in the publication process

I knew from experience that there are multiple steps involved in getting your research published: choosing a journal, preparing an article manuscript, submitting it to an appropriate journal, peer review and responding to peer review and, ultimately, publication. However, my time as a researcher had been quite a long time ago and things have changed. So, I could do with a reminder of how it all works. And I was not disappointed.

All steps involved were discussed in depth. Consequently, I now have a much better understanding of the route to publication. I think it is helpful to be aware of what happens before and after submission because it clarifies where manuscript preparation fits into the process. It reminded me of my teacher training, when I had to do something similar. I was training to teach children aged 7 to 11 and we had to spend time in schools with children aged 5 to 7 and in schools with children aged 11 to 14 to find out where the children came from and where they were moving onto.

2. How to prepare a manuscript for submission

Manuscript editors can help with correcting spelling, punctuation and grammar, ensuring good sentence structure so that the author’s message can be understood by the reader, and formatting the manuscript so that it complies with the journal’s instructions for authors.

There may be many reasons for manuscripts not being accepted for publication: some related to the study itself or the manuscript not falling within the scope of the chosen journal, and others related to language errors or not adhering to the journal’s instructions for authors. I wish to help researchers with the latter and, in doing so, improve the chances of their manuscript not being rejected at first sight and, therefore, being considered for peer review. Spelling, punctuation and grammar must be perfect – or near perfect. As editors we know how to spell or if we are unsure, we can consult a dictionary. We also know how to use punctuation and grammar correctly. But there is so much more to creating a well-presented text. Do we know what to do with numbers in a manuscript? In which situations is it appropriate to use percentages? And what about levels of precision? Is there a space between the percentage sign and the number? Or between the number and the unit? What units to use? And are we using the correct multiplication sign? No, not the letter x. All this may sound rather dull, but it wasn’t. The explanations of the finer points were interspersed with engaging anecdotes. As a bit of a perfectionist, it was music to my ears. I was very happy to have all the above questions – and many more like those – answered.

It didn’t stop there. Citations and references were also discussed in detail, as were the different reference styles. Again, multiple examples showed the many ways in which citations and references can be formatted. That’s why it is so important to look at the instructions for authors for the particular journal you wish to publish in and its recent issue. They all seem to have their own preferences, for example, in author-year citations, a comma before the year or not and in numbered citations, the number in italics or roman. There were too many options to mention. I found out though that I truly enjoy looking at texts to that level of detail.

3. How to prepare tables and charts

Many academic articles include tables with numerical data. But do we know what makes a good table? What headings should be used? Should numbers be left-aligned, centre-aligned or right-aligned? And what to do with cells that have no data? I never knew there was so much to designing a clear and informative table. Many examples were shown to illustrate what makes a good table and why some tables are just too difficult to interpret.

We can ask the same question about charts. What makes a good chart? How do you know which chart is right for your data? As a tutor of maths, biology and chemistry I am familiar with the common types of chart and I know which one to use when: line graphs, box plots, bar charts, histograms, pie charts, kite diagrams and scatter graphs. But there are many more. Here I was introduced to some new charts – at least new to me. For example, I had never seen violin plots, heat maps and Coxcomb charts before. Thanks to the examples shown and the detailed explanations, I now understand much better which chart to use for what type of data and I have an insight into the large variety of tools available for creating any type of chart. Although I do not need to know how to produce tables and charts, I want to know what they are telling me.

4. How to improve effective writing skills

I know that to be a good editor, it is essential to also be a good writer. Effective writing is a skill and, therefore, it can be learnt and, of course, improved. To write effectively you must write in such a way that your readers understand what you are trying to tell them. The writing needs to be clear, concise and accurate. The course offered much advice on how to tackle writing in a systematic way and how to become an effective writer, and that it is normal for a good piece of writing to have gone through many drafts.

It was pointed out that writing skills can also be improved by extensive reading, in particular books by good writers. That’s certainly not a chore. I was especially excited about the Very Short Introductions series by Oxford University Press and the shortlist for the Royal Society Science Book Prize. These have introduced me to a lot of books I would otherwise not have read.

What I liked and why

I enjoyed the course immensely; the breadth and depth of information that was presented was extraordinary. Almost too much to grasp first time around. If anything hadn’t fallen into place, we could watch the recordings that were made available to all attendees.

What I found particularly helpful is that the trainer, Yateendra Joshi, showed so many examples. He explained very carefully how some things didn’t work, which made it much easier to understand the points he was trying to make. And if you still had questions, you could ask either during the session or by emailing him – I frequently did and always received a helpful answer within a few hours. Or you could try to find the answer yourself, since every session concluded with a long list of recommended reading.

After taking the course, many aspects of the editing and writing process have become much clearer. And I have this extensive list of helpful sources that I can turn to.

I hope this post has given you an impression of what the course has to offer. If you have any questions about the course or anything you think I may be able to help you with, feel free to

|

Blog post by: Monique Oude Luttikhuis Website: tuitionandtranslationservicesspalding.com LinkedIn: monique-oude-luttikhuis |

Written by: Lizzie Kean

Published: 28-11-2024

I’m sure a lot of people recognize this: you love to write but you can’t seem to find the time. A write-along, by analogy with the MALs and CALs (make-along; crochet-along) from the world of handicrafts and of course the good old sing-along, is a big friendly nudge to help you find that time. A write-along means working on the same project at the same time as other participants. You get instructions one at a time, sometimes every day, but in the case of the first SENSE Write-along that was launched last April, one a week, for twelve weeks. And by the end of that time, you will have written a short story! The assignments are designed to cost you no more than ten to fifteen minutes in actual writing time.

As with all activities you have to find time for, like going to the gym or weeding the garden, actually getting started is the hardest part. With the write-along, most people are hooked on completion of the first assignment. As language professionals, whether translators, copy-writers, editors, or working in other directions, we have to be good writers too. And practising is the best way to keep that skill sharp.

We started the SENSE Write-along with 31 participants and only three dropped out after the first week or two (they shall be nameless here). As far as I know, all the other participants completed the whole process. Sadly, only five chose to post their stories in the section of the Forum set aside especially for them. But those five made me very happy. When you read all of the texts, it’s hard to remember that they were all written according to the same assignments. That’s part of the fun of a write-along and of reading the resulting stories.

A big thank you to everyone who took part this time!

I will be starting a new write-along on 3 January 2025 and I invite you to participate (send an email to

The writers of the first write-along who agreed to their texts being published will see them appear sometime on the SENSE Blog, but in the meantime I leave you with the short story written by Sally Hill.

A walk in the park

By Sally Hill

Jeannie always let Prince off his leash when they reached the park, and just could not understand how he had ended up at the edge of the duck pond with a broken leg and the life sucked out of him. As she kneeled next to his lifeless body, her neighbour Brenda – uncharacteristically dressed in a boilersuit – approached to offer her sympathies.

Jeannie was surprised at her concern given that Brenda had never previously given either Prince or Jeannie the time of day – and had certainly never been so neighbourly. In response to Brenda’s questions as to what had happened, Jeannie could only reply that it had to have been something to do with the group of teenagers who were always hanging around under the oak trees near the pond. Brenda agreed, but as she helped Jeannie clean the mud off Prince’s coat and wrap him in a reusable shopping bag, Jeannie couldn’t help noticing a stain on Brenda’s boilersuit – a dark red stain that was not mud and looked suspiciously like blood.

After returning home from the vets to dispose of Prince’s muddy body, Jeannie mentioned her suspicions to her boyfriend Chris, and the rumours she’d heard that Brenda was a notorious dog hater; but she was not able to persuade him that Brenda was the culprit. Was she just imagining things after all?

There was only one thing for it – she decided to go round to Brenda’s house on the context of borrowing a cup of honey, to see if she could pick up any more clues. To Jeannie’s surprise, her repeated knocking kicked off a great deal of barking from behind the door, and when she peered through the double glazing to take a closer look, she counted what appeared to be nine puppies of various breeds, all in small cages!

As she later related to Chris, still shaking from her subsequent confrontation with her neighbour, Jeannie could never have imagined how right she had been to be suspicious – who would have thought that Brenda was in fact a vampire who survived on dogs’ blood. Chris was fascinated and amazed at this revelation and managed to persuade Jeannie to invite Brenda to join them at that Sunday’s Hollywood Vampires concert at the O2 Arena – imagine having a real vampire alongside him while listening to his favourite band!

The evening was a great success and from then on, the three of them were firm friends; although you will not be surprised to learn that Jeannie and Chris never invited Brenda to join them when taking their new puppy Bounce for his walk in the park.

|

Blog post by: Lizzie Kean Website: www.lizziekean.nl |

Written by: Liz van Gerrevink-Genee and Joy Burrough-Boenisch

Published: 19-11-2024

On 11 October, UniSIG was treated to the online talk ‘Making footnotes and bibliographies plain – decoding, readability, Zotero/AI, consistency’ by former SENSE member (and past convener of FINLEGSIG) Dr Stephen Machon, who is a highly experienced legal English editor/reviewer and trainer. He spoke on a necessary part of the scholarly and academic machinery of publications: footnotes and bibliographies. Having clarified that the information provided under the headings ‘Bibliography’ and ‘References’ is essentially the same, as both refer to a list of sources, Stephen pointed out that footnotes (and endnotes) may also indicate the sources substantiating an assertion in the main text as well as provide additional information or opinions not central to the narrative. Bibliographies and footnotes are both important because they contribute to an author’s academic standing.

There is no one agreed footnote or bibliographical entry style, which leaves editors, proofreaders and reviewers prey to the vagaries of publishers’ editorial staff and their style guidelines. Our job as editors is to ensure consistency and readability not only in the narrative but also in the footnotes and bibliography. Being aware of where we can make the coded language of footnotes and bibliographies plain can contribute significantly to the readability of a scholarly publication, whether an article, monograph, or PhD thesis.

One noteworthy difference between the Dutch and English footnote conventions that Stephen drew our attention to relates to footnote numbering: the Anglo convention is for the numbering to begin afresh for each chapter, but the Dutch convention is to continue numbering consecutively throughout the thesis or book. This can result in very unwieldy footnote numbers and vastly complicates any renumbering needed after removing or adding a footnote, so Stephen recommends advising Dutch authors to follow the Anglo convention.

Stephen showed examples of reference styles, explaining that he’s punctilious about ensuring consistency in the bibliographies and footnotes of the law PhD theses he edits, and is paid well for doing so. Lively discussion ensued about whether when dealing with a monograph thesis or an article intended to be part of a compilation thesis a language professional should rigorously copy-edit the bibliography or reference list and the citations. Alice Lehtinen’s comment in the meeting chat summarizes the feelings of many of the 17 attendees: ‘I think it depends on what your role is, on what you’ve agreed to do. In my case, I avoid checking bibliographies etc. like the plague, but I make this clear to the client. I consider myself the language expert, and that these things are down to the client to check.’

Stephen has kindly agreed to allow his PowerPoint® presentation to be sent to interested SENSE members, so if you missed this lively and informative meeting or would like to be reminded of what Stephen covered in his talk, please email Joy (the UniSIG convener).

|

Blog post by: Joy Burrough-Boenisch LinkedIn: joyburroughboenisch |

|

Blog post by: Liz van Gerrevink-Genee Website: www.transl.nl |

Written by: Cathy Scott

Published: 7-11-2024

Mysterious? You must be joking. Examples of copywriting are all around you, clamouring for your attention, demanding your approval, prising open your wallet, changing your mind and appealing to your basest instincts. The bombardment of commercial – and increasingly political – messages starts as soon as you open your eyes and ears in the morning, continues on billboards and bus sides as you wander down the street, and even unashamedly follows you into the loo. (Do remember to disinfect your phone on a regular basis.)

Yet members of this esteemed organization are often mystified as to what copywriting actually entails, let alone how to actually do it. (Preferably in exchange for more money than is generally available for translating or editing other people’s texts.) So here’s a quick overview of a vast and changing landscape.

What copywriting is

The term for text on an advertisement is ‘copy’, and the way it originates is by someone writing it. (Remove the silent ‘w’, and you’re in legal territory instead.) In general, copywriting simply involves coming up with words to persuade a target group to buy the goods or services of a particular client. It’s the advertising industry’s expression of the latest exhaustively determined marketing position. Unlike proper journalists, whose job is to tell a story objectively, copywriters are happy to present only one side of the argument while conveniently forgetting the rest. At one advertising agency I worked for, I was so utterly convinced by the studies presenting the superior benefits of medicated talc X versus cream Y for treating nappy rash that I wrote an entire consumer leaflet singing its praises. Imagine my surprise when, a few years and ad agencies later, I had to do the same thing again – only this time for cream Y, which came complete with equally compelling scientific reports drawing precisely the opposite conclusion.

Where you can find it

One reason for the confusion surrounding copywriting is its sheer variety and ubiquity. At the start of my glorious career 40 years ago, one would be briefed to write encouraging words for a finite group of media types: TV commercials (on a lucky day), radio spots, printed products (newspapers, magazines and direct mail) or posters. Since then, the number of possible channels has exploded, although the bread-and-butter work consists largely of websites, social media posts, emails, intranet updates, e-brochures and print-on-demand magazines. You can’t deny that many trees have breathed a sigh of relief.

The short and sweet of it

Yet one aspect hasn’t changed in the slightest: all of these diverse communications are expected to hold true to the key brand concept, which is usually summarized in what outsiders call a slogan (a term that makes insiders wince) or what we professionals knowingly refer to as a strapline, endline or tagline. The most successful of these tend to be short and sweet: ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz’ (remember that one?); ‘Reassuringly Expensive’ (Stella Artois); ‘Just Do It’ (Nike); or ‘Think different’ (Apple). You may also come across some hilariously optimistic ones, such as ‘Let’s make your home special’ (IKEA) or less innocent examples, such as ‘Take Back Control’.

Yet one aspect hasn’t changed in the slightest: all of these diverse communications are expected to hold true to the key brand concept, which is usually summarized in what outsiders call a slogan (a term that makes insiders wince) or what we professionals knowingly refer to as a strapline, endline or tagline. The most successful of these tend to be short and sweet: ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz’ (remember that one?); ‘Reassuringly Expensive’ (Stella Artois); ‘Just Do It’ (Nike); or ‘Think different’ (Apple). You may also come across some hilariously optimistic ones, such as ‘Let’s make your home special’ (IKEA) or less innocent examples, such as ‘Take Back Control’.

Concepts and copy

Such deceptively simple phrases usually form part of the core advertising concept for which several ad agencies eagerly pitch every few years. Creative teams (each consisting of a copywriter and art director) battle it out to distil hundreds of pages of indigestible marketing bumph into a tasty little snack. Sometimes all these efforts boil down to a typical Holy Trinity consisting of headline + visual + strapline; sometimes the headline’s merely the product name; and sometimes the concept is further condensed into merely a picture of the product (or logo) with the genius new brand line.

From concept to campaign

Once that rather fun conceptual part is over, it’s time to craft the rest of the communication campaign. This can roughly be divided into B2B (business-to-business), B2C (business-to-consumer) and even C2C (consumer-to-consumer) items. Some of these, such as brochures and websites, will need long, descriptive explanatory copy that needs to be carefully structured. Others, such as Twitter (now X) posts and the more minimalist kind of press ads, will focus on conveying a key message or brand value in just a few words. But wherever you’re replacing grey lines (the ones drawn by the designer to indicate where you’re allowed to play) with actual text, you need to ensure that your words either complement, explain or add an extra dimension to the visuals that accompany them. This applies throughout the customer journey, which is the term used to describe all the interactions that a member of the target audience has with the product before, during and even after the purchase itself. No communication channel, no matter how small, should go to waste.

Once that rather fun conceptual part is over, it’s time to craft the rest of the communication campaign. This can roughly be divided into B2B (business-to-business), B2C (business-to-consumer) and even C2C (consumer-to-consumer) items. Some of these, such as brochures and websites, will need long, descriptive explanatory copy that needs to be carefully structured. Others, such as Twitter (now X) posts and the more minimalist kind of press ads, will focus on conveying a key message or brand value in just a few words. But wherever you’re replacing grey lines (the ones drawn by the designer to indicate where you’re allowed to play) with actual text, you need to ensure that your words either complement, explain or add an extra dimension to the visuals that accompany them. This applies throughout the customer journey, which is the term used to describe all the interactions that a member of the target audience has with the product before, during and even after the purchase itself. No communication channel, no matter how small, should go to waste.

Welcome to your world

As a copywriter, your job will be to peek under the surface of an astounding array of different organizations in order to glean just enough knowledge to write about their business, products, services or aims without frying your brain. Once in a while, having found your niche, you may spend your time exploring a much-loved specialism in nerdy depth with a favourite client. You’ll learn a lot about social trends, innovations, economics and people along the way. Hopefully, you’ll also gain useful skills such as keeping a straight face upon being informed by market researchers that the persona epitomising the core user of Brand Fab is Julie, a mid-thirties career woman who lives in an untidy semi-detached house in a working-class area with a slightly incontinent, elderly Labradoodle called Muffin.

Write here. Write now.

If you’re interested in getting into this game, you need to be more than a wordsmith. You should also be able to create visual concepts, understand commercial goals, adapt your writing style to the agreed tone of voice, and ensure that everything you write is fit for purpose. Some clients may be impressed by a CV featuring a Bachelor of Arts from a famous alma mater, but what they’re really looking for is a portfolio of copywriting examples (which, in the beginning, will be private masterpieces that you would have written if anyone had been discerning enough to hire you). Meanwhile, look around you at the myriad of existing examples, study it all to work out how it’s done, and challenge yourself to learn how to do it better. For instance, you’ll probably notice that lots of long-copy items finish off with a Call To Action. So start today!

|

Blog post by: Cathy Scott LinkedIn: cathy-scott |

Written by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy

Published: 30-10-2024

Freelance translator Mahala Mathiassen (LinkedIn: mahala) joined SENSE in September. She is currently based in Mandal, on the south coast of Norway, and has been translating from Norwegian to English for the past 15 years. I invited her to share some of her story and she accepted with enthusiasm. Here’s what she had to tell.

Freelance translator Mahala Mathiassen (LinkedIn: mahala) joined SENSE in September. She is currently based in Mandal, on the south coast of Norway, and has been translating from Norwegian to English for the past 15 years. I invited her to share some of her story and she accepted with enthusiasm. Here’s what she had to tell.

Were you born in Mandal? Can you tell us a bit about where you are from?

I’m a British citizen and a permanent resident of Norway. I was born in Colne in Lancashire, but moved around quite a bit in the UK. I obtained an Honours Diploma in French, Spanish and Business Studies from Mid-Essex Technical College & School of Art in Chelmsford (now Anglia Ruskin University), and subsequently held administrative positions in the UK before mainly working overseas in Libya, Zambia and Spain. After some years in Norway, we relocated as a family to the US in 1982 when I was employed on a four-year contract with the US subsidiary of a Norwegian-owned company. After returning to Norway, I established a company offering tourist information, coordination of patient transport and translation services, and subsequently decided to concentrate on translation services and established my current company in 2008.

How did you arrive at translation as a profession?

I have always had an interest in languages. I gained translation experience at college, and I was able to practice my Spanish working for a British property company. I arrived in Norway with no knowledge of Norwegian and, without a work permit and with two small children, I had to learn by doing. Eventually, I obtained a position in the international marketing department of a consultancy firm, where my language skills proved useful. I have since passed the Chartered Institute of Linguists exam and obtained their Postgraduate Diploma in Translation. I took short courses in translation to and from Norwegian at the University of Bergen and passed their Advanced Test in Norwegian at the level of a native speaker. Additionally, I qualified as a member of the Institute of Translation and Interpreting in the UK and I regularly attend CPD courses and webinars arranged by various translation associations.

What kind of projects have you worked on?

The first Norwegian to English project I worked on was as in-house translator for a consultancy firm and involved translating a university textbook on geographical information systems published by John Wiley & Sons in collaboration with the author, Tor Bernhardsen. I was not credited as the translator, but the translation received positive reviews. My first project as a freelance translator involved translating a series of articles related to causes of kidney poisoning for a medical researcher at a Brazilian medical centre. This was a pro-bono project, with a nominal payment of $5; however, I was credited as the Norwegian translator on the final report. One of my earlier paid projects was a scientific article for publication relating to fisheries for a senior research scientist at SINTEF, Trondheim. Projects for agencies have covered a wide range of subjects, but I eventually specialized in financial, legal and business documents, including annual reports and accounts, contracts and agreements. I can credit my past and present business experience and background for leading me in this direction. I have also translated and certified personal documents, birth certificates, university transcripts and the like.

How did you learn about SENSE and why did you decide to join?

I first became aware of SENSE on Facebook and was at the time considering moving on from translation to proofreading and editing, and I was also motivated by the fact that I did not feel any sense of belonging to larger international translation associations. I also hoped to be able to contribute in some way.

What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

I am working at keeping my green plants alive, I enjoy cooking and am interested in Scandinavian vintage furniture and interior design. I tend to enjoy more intimate social gatherings, art and photography exhibitions, and regularly tune in to English language news channels, and enjoy listening to classical music and some pop music.

Do you read a lot? Can you recommend some books?

I used to read a lot of English and Norwegian literature, especially during my period of employment as the manager of a public library but have lapsed somewhat. Some Scandi Noir but also a variety of other authors – some in translation, such as Elena Ferrante. Nowadays, I tend to read more specialized publications, for example The Economist, and articles and blog posts on LinkedIn, as well as articles in Norwegian and English newspapers and magazines, and I listen to podcasts on various topics of interest.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Written by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy

Published: 17-10-2024

Sworn translator Dutch to English and long-standing SENSE member Paula Truyens (in the photo standing between former SENSE members Joan Shoheb and Vivien Cook in Inverness last year) has been pondering whether to emigrate to Vietnam or Cambodia to teach English to small kids. But changing countries or even continents is not new to her, having lived in South Africa, Lesotho, the Netherlands, Spain and now France. In the following interview, she expands on what she calls her ‘nomadic genes’ and why she is considering Asia too.

Sworn translator Dutch to English and long-standing SENSE member Paula Truyens (in the photo standing between former SENSE members Joan Shoheb and Vivien Cook in Inverness last year) has been pondering whether to emigrate to Vietnam or Cambodia to teach English to small kids. But changing countries or even continents is not new to her, having lived in South Africa, Lesotho, the Netherlands, Spain and now France. In the following interview, she expands on what she calls her ‘nomadic genes’ and why she is considering Asia too.

I understand that you were born in South Africa. Can you tell us a bit about where you are from?

Sometimes I tell people I was born in a big barn in South Africa. Imagine the world’s first heart transplant being performed in a barn! That is, of course, Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town. My grandparents emigrated to South Africa in the 1950s. Work was quite scarce after World War II and the Dutch government encouraged families to immigrate and financially assisted them. Opa had learnt the art of making sausages and deli meats in Germany, where he had been put to work by the occupiers. He used to smuggle thin slabs of bacon wrapped around his belly back home to Amsterdam. I wonder what would have happened had he been found out… His sausage-making skills stood him in good stead to co-found a butchery in Cape Town. As a small tot, the European deli meats didn’t really appeal to my taste. It was with bits of biltong and boerewors that Opa won my affections.

My grandparents sent their children to a Catholic school, where all the classes were in English and you could take Afrikaans as an optional subject. Once the brood had mastered English, they took to speaking that at home rather than Dutch – mostly so that ‘ma en pa’ wouldn’t be able to follow most of what they were saying.

My mother went to Cape Town University, where she met my father. Their relationship was very casual and brief and I didn’t get to know him that well. After he’d moved to Long Island (New York) in the 1970s to start practising as a paediatrician, I visited him in New York City – just before 9/11 – and learnt that he had both Scottish and Irish ancestry. I also seem to have inherited my love for ballroom dancing and all manner of fauna from him. He even had a spider collection.

Despite strict apartheid rules during the 1960s and 1970s, there were non-white students at the university, and a chance encounter between my mother and Elisabeth, a Xhosa student, radically changed the course of our lives. Elisabeth invited my mother to her home in one of Cape Town’s segregated townships, planting in my mother the seeds of resistance to apartheid. She took part in silent anti-apartheid protests at the university and gave covert art workshops for children in the townships of Langa and Gugulethu with a group of students. These ‘subversive political activities’ didn’t go unnoticed and when she found out that her phone had been tapped, decided to pack up the bare necessities and leave South Africa. Fortunately, she was offered a job as an English teacher at Masitise High School in Lesotho, in the Quthing district (yes, a click word!). We didn’t learn until much later that the principal, Frank Lebentlele, had been Nelson Mandela’s zoology teacher at Healdtown, a mission school in the Eastern Cape (South Africa). To this day I have fond memories of Mr Lebentlele, who welcomed us into his family, accommodated us for the first few months and taught my mother the fine art of gardening.

In 1982, after I’d completed my O levels at Machabeng College in Maseru and the SA Defence Force had in that same year crossed into Lesotho to liquidate members of the African National Congress political party (killing a total of 42 people, including innocent bystanders), my mother felt it wise to uproot and move again. But this time not only to another country but to another continent. As my mother had always kept her Dutch nationality, the Netherlands was the logical choice.

You have been a SENSE member since 2010. Where did you hear about the Society? Were you already living in the Netherlands by then?

Yes, I was already living in Utrecht and had just started my first job as an in-house translator, in Zeist. I actually studied biology at Utrecht University, fruit flies to be precise, but like many students in my year I ended up in a completely different profession. One friend is now a choirmaster and conducts a small orchestra and another friend from my year writes code. At some point in my studies the idea of working in a lab, grinding up fruit flies or doing any kind of research on animals, became ever less appealing. At the time I had a side job as an attendant on the Alpen Express train, as I had to earn money to supplement my student grant. One of the travellers (to Bourg St. Maurice, if I remember correctly) struck up a conversation and asked if I enjoyed my job. I told him it was only a side gig and that I’d managed to get it because I spoke Dutch, French and English. I was studying biology but hoped to pursue a career in writing or translating in STEM fields. ‘So, you’re a biology student and English is your mother tongue… I happen to need a small leaflet on antibiotics for plants translated from Dutch into English. Might that interest you?’ It was my first ever translation job and the 900 guilders I got for it seemed like a fortune at the time. Don’t ask me about the quality, but the client seemed happy.

Soon after, I enrolled in a three-year part-time translation course at Hieronymus Hogeschool. Shortly after obtaining my diploma, I was sworn as a Dutch to English translator at the District Court of Utrecht. In that same year I was hired as an in-house translator by an agency in Zeist. A few years ago I learnt that the company had been bought by Powerling and many staff members were let go.

A colleague at work, former SENSE member Jill Whittaker, told me about SENSE and if I remember correctly, we both joined at the same time.

I believe you are currently living in France. Why did you decide to settle there?

This is turning out to be as much about my mother as about me, but I suppose that’s inevitable when providing some background for the ‘nomadic genes’. She never really settled in the Netherlands and in 1987 decided to move to a sunnier climate. A friend of hers had a small holiday home in France, in the foothills of the Pyrenees. After a visit to her friend she fell in love with the area, especially with the open spaces and mountains that reminded her of our beloved Lesotho. It is said that Tolkien’s inspiration for his Middle Earth books was born in the Drakensberg mountain range between Lesotho and KwaZulu-Natal. Some of the mountain walks I’ve done with friends in the Pyrenees, past wild horses and tranquil mountain lakes, made us wonder if we might come across a trio of petrified trolls.

After working for the translation agency in Zeist for nine years and an agency in Rotterdam for four years, I was itching to travel again but also spread my wings and become a freelance translator. ‘Why not move to Sarrecave?’, my mother suggested. ‘I’ll divide my two-acre piece of land into three smaller plots, you have the bottom one, your brother the top one and I’ll stay in the middle one with the house.’ A former sheep shed and a 1970s caravan would be enough to get me started, we figured. Thanks to the French way of doing things, it was only ten years later that the new zoning plan, which had been in the works for as many years, was finally approved by all the relevant organismes publics and I could build a small wooden chalet on my piece of land. Living like a tsigane, or ‘traveller’, for ten years meant I was able to save enough money not only to buy a small studio on the Spanish coast but also to put up the chalet without needing a loan. It was only last year that the final project – a septic tank – was completed and at long last I had a flushing toilet and hot shower. No, I lie – last week a neighbour and I manoeuvred a 1000-litre rainwater harvesting butt into place and connected it to the spout.

I guess you now speak Afrikaans, English, Dutch, Spanish and French. Is that so? Do you work in all those languages?

Because I went to an English Waldorf school in Cape Town, I never learnt Afrikaans, although my mother could speak it a bit. We always spoke English at home and in Lesotho I learnt Sesotho as well as a bit of French, thanks to Swiss friends with whom we shared a former colonial house in Maseru (Lesotho was once a British Crown colony).

My French keeps getting better, having learnt it at a fairly young age and now being immersed in it. But my Spanish is also coming along nicely, as I regularly go to my studio near Malaga and even lived and worked there briefly. After two years I decided I much preferred the uncomplicated French autoentrepreneur regime for the self-employed to the almost Kafkaesque autonomo regime and other formalities in Spain. The nomad wandered up north again.

I only translate from Dutch into English. Although I speak Dutch almost fluently and am more than confident when communicating with clients in Dutch, I’ve never considered translating into Dutch. There are always imperfections in my written Dutch, as I never learnt it properly at school and am constantly having to look up if it’s a ‘de’ or ‘het’ word or ‘bedoeld’ or ‘bedoelt’. I had to struggle to get a 6 for Dutch at high school in The Hague (pre-university education). My grade for English was 9 and I got a 7 for French.

Have you perceived a shrinking in demand for traditional translation work due to AI? Is that at the core of your search for a new path in Cambodia or Vietnam?

Yes, especially from translation agencies. Over the past four or five years, a number of agencies I used to work for have been bought by the usual suspects in a series of mergers and acquisitions. Before then, the rates were good and communication with the project managers, who tended to stay with the agency for several years, was always personal and pleasant. This started to change, with jobs being offered through impersonal job notification emails sent to several translators at once. Whoever clicks first on ‘accept’ in the agency’s online portal gets the job. Fast-forward to now and the jobs are almost exclusively ‘Translation 2.0’, a fuzzy euphemism for correcting disjointed machine translation (MT) output at pitiful rates. For a while I took on the occasional Translation 2.0 job when business was slow but decided last year that it wasn’t worth it. I’m still registered with one of those agencies but as I’ve not heard from them for some time, I’m sure I’ve ended up on their ‘too expensive, only use in an emergency’ list.

Luckily, I still get a steady flow of work from a number of boutique agencies and direct customers, so I’m not panicking – yet. It’s actually a nice way to ease into partial retirement. The reduced workload gives me more time to focus on other projects I’ve been wanting to take up. Refining my gardening skills (thanks Mom and Mr Lebentlele). Improving my French. Or finally starting a CELTA course in Toulouse with my CPD budget… for a possible new adventure in Cambodia or Vietnam. I think it’s those nomadic genes but also the desire to branch out into something different. Migrate to a new continent and teach English to young kids. Although I’ve heard that the booming international start-up ecosystem in Malaga is in need of local workers whose English is up to the task. Mind you, I’d have to navigate those Spanish formalities again.

A few months ago, you posted on the Forum about your mother’s teaching to small kids in Darjeeling, India. Can you tell us about that? Are you considering India as well?

My mother and I travelled to India in 1989 and spent five weeks trekking from Mumbai to Ganeshpuri, Pune, Goa, the Thekkady nature reserve, Kerala, Bengaluru and back to Mumbai by bus and train. I remember the long wait at dreary, soulless Charles de Gaulle for our connecting flight to Toulouse after all the colour and vibrancy of India. The beautiful salwar kameez I’d donned that morning suddenly looked entirely out of place among all the grey suits in the aeroport. India was unlike any European or African country we’d been to. We were enchanted.

Just after I moved to France in 2009, my mother was invited to Darjeeling by her French yoga teacher. He was involved in a number of projects there and they were looking for someone to help improve the level of teaching at a Tibetan primary school in Kalimpong, a small town not far from Darjeeling. My mother had written a number of educational readers for Macmillan, later Nelson Thornes, so she agreed to give it a try. Initially she helped one of the teachers bring more structure into her English lessons. She saw that the school had few to no books for the children to read and that good quality readers were not only expensive but also not always culturally adapted. It didn’t take long for her to jump into writing some readers herself. And if she could get friends and family to help with the costs of printing, the booklets could even be free.

I’ve kept in touch by email with Yangzom, the English teacher my mother worked with. After my mother passed away in 2021, we decided to honour her memory by keeping the reader project alive on www.lotusreaders.com. I’ve uploaded a few of the readers and hope to have them all online by next year. My mother had started writing Gesar of Ling, a story based on a Tibetan heroic epic. Yangzom reckons I could easily finish the story and that it would be wonderful… maybe I will. In any case, I would love to travel to Darjeeling to see what inspired my mother and meet the people she knew. I occasionally get an email from a former pupil who says it was Hannie-la who encouraged them to do well at school and now they’re training to be a teacher.

What do you like to do when you are not translating or travelling?

What do you like to do when you are not translating or travelling?

I love my daily walks in the fields and woods around our village with my dog Jo, who pitched up out of nowhere ten years ago and decided to adopt me. My garden also takes up a lot of time, especially now that I’ve started a vegetable plot and my fruit trees, hedges and meadow lawn need to be kept in check on a regular basis. I used to do aikido here in our tiny village in La Profonde France but gave that up when I moved to Spain. It’s something I’ve been considering taking up again, although qigong or tai chi is probably more doable for me. Aikido was great fun but also quite hard.

My reading group of Dutch expats gets together once every two months to discuss a book but mostly to enjoy a meal and good wine afterwards. Where possible I get the English translation of the book we will be reading. Is that cheating?

Can you recommend us some reading?

I recently read two of the books suggested in our reading group in French, Simone de Beauvoir’s ‘Les Inseperables’ and ‘En finir avec Eddy Bellegueule’ by Édouard Louis. I was pleasantly surprised by how much I understood. And reading the books in French seemed to give me a better feel for the characters and cultural context. The most recent book we discussed was ‘The Tobacconist’ by Austrian writer Robert Seethaler. First I read it in English, then I watched the film in German. I must say I enjoyed the film more than the book, probably because of the language and exquisite cinematography (Der Trafikant). Some of you will know Marcel Lemmens from Teamwork, who recommended this beautiful book on LinkedIn. Thanks Marcel!

We’re currently reading ‘Buat’ by Jean-Marc van Tol – a doorstop of a book about the relationship between raadpensionaris Johan de Witt and his ritmeester Buat, Henri de Fleury de Coulan (1622–1666). It’s only been published in Dutch, so it’s just as well I’d already decided to read it in Dutch!

Also worthy of mention is Rutger Bregman’s ‘Humankind: A Hopeful History’. I finished it in one go and, as Stephen Fry so aptly put it, it is ‘hugely, highly and happily recommended’.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Written by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy

Published: 3-10-2024

The University of Amsterdam specifies what a special interest group (SIG) is for, stating that ‘Within a SIG, interested parties come together to exchange, develop and apply knowledge and experience. In doing so, a SIG focuses on expertise and networking around a specific theme.’

Currently, SENSE has ten SIGs that meet a few times a year in person or online. SIG meetings are open to SENSE members and non-members alike, and are announced on our SENSE events calendar.

This week I invite you to meet the Starters SIG and its conveners, Anne Oosthuizen (left in the photo) and Becky Tomas (right), who define this SIG as ‘a community of newcomers to SENSE and to the industry as a whole’.

I believe the Starters SIG began in 2020. Is this correct? How did it all start?

It all started during the SENSE Conference in 2020. I (Anne) had joined SENSE the year before and in 2020 I joined the Executive Committee as SIG and Social Events Coordinator. At the time I was approached via Zoom by Danielle Carter, who was equally fresh-faced and looking for other newcomers to the industry to bond with. As it turned out, we lived very close together in Amsterdam Oost and decided to meet up for drinks. We also invited Martina Abagnale, who was also new to SENSE and was being mentored by Jenny Zonneveld. The three of us really hit it off and decided, right there during that first meeting, to propose a new SIG. Being SIG coordinator, I had been toying with the idea of a SIG specifically for those starting out – mainly because I felt that some of the knowledge about the industry was sometimes a little dated and didn’t always benefit newcomers. Together, we came up with the concept of the Starters SIG as a platform for peer-to-peer learning and a safe space for horizontal knowledge sharing.

Can you describe your backgrounds and what made you volunteer as conveners?

Anne: In 2020, I had just finished my MA Linguistics: Translation in Theory and Practice at Leiden University. I was working as an in-house translator at AzTech, a technical translation agency, under the guidance of Ellen Singer. Martina was just starting out as a legal translator, and Danielle was coming at the language industry from a completely different angle: museum studies. All three of us were new to freelancing and to the industry as a whole, and found it extremely helpful talking about our respective obstacles with people who were going through the same thing – but sometimes ran into very different problems. So, we decided to expand our platform and formalize our collaboration. We had a good run, but when Danielle and Martina took a step back from the SIG’s activities, I found it hard to continue the Starters SIG on my own. However, I was reluctant to just let it go. The Starters SIG was kind of my baby. That’s why I was overjoyed when the current SIG and Social Events Coordinator, Becky Tomas, volunteered as co-convener at last year’s Professional Development Day (PDD). It’s been really lovely running the SIG together – I think we make a great team!

Becky: My story is quite different! Since immigrating to the Netherlands in 2012, I’ve been a freelance dance instructor (Lindy Hop, specifically), and I’ve been busy running a dance school in Rotterdam.

I had graduated with a Bachelor of Arts with Honours degree in English Literature back in 1999, and although I had dabbled in editing and proofreading over the years, other work opportunities always seemed to come along. So, for quite a long time I did not pursue this avenue of interest.

Sitting at home during the Covid pandemic, with the dance school closed and not a lot to do, I decided this was the perfect time! I stumbled upon SENSE online, attended the Annual General Meeting (AGM) in 2023 and jumped into the role of SIG & Social Events Coordinator.

Anne and I met at the 2023 PDD, and the rest is history; the Starters SIG is going swimmingly!

What’s the main purpose of the Starters SIG?

The slogan of the SIG is ‘run by starters, for starters’. This SIG provides a safe space where members can network, share their experiences, and ask for tips and advice from their peers, who are all in the same boat (or may have just managed to clamber ashore). In addition to serving SENSE’s newer members, its aim is to support existing members who might be branching out into new territory. We also hope to attract potential new members to SENSE with our starter-geared topics and low-key vibe.

What kind of discussions or events are on the table?

In the past, we have organized meetings on finding clients, pricing your work, web design, and LinkedIn marketing. This year, Becky and I decided to approach the revival of the Starters SIG from a starting-point perspective: what would you want or need to know when you’re just getting started or have recently made a career switch? In upcoming meetings, we’ll cover money management, branding and rebranding, taxes, and more!

Can you walk us through some Starters SIG meetings?

The Starters SIG likes to organize meetings that aren’t strictly top-down, meaning that they are either guided group discussions or group discussions following a short, often interactive, presentation. During our meeting in February, business coach Miranda Apeldoorn spoke about finding your business focus. We had many fantastic contributions from the group and I think many of us came away feeling quite inspired.

In April, Martina Abagnale gave the talk ‘Money management with Martina’, on how freelancers like us can manage the money that comes in our bank account and what to do with it once we’ve earned it.

In our last meeting in July, Anne presented her talk ‘Personal branding: Lessons learnt through trial and (t)error’. For those who missed the talk about branding and marketing, you can read Linda Jayne Turner’s blog post about it.

Do you have plans for the future of the SIG?

Anne: We plan to keep up our regular meetings every two to three months.

Becky: We had our first meeting as conveners in Bagels & Beans in Leiden, and between mouthfuls of hummus we managed to plan events for an entire year. We’re really excited about our meetings and speakers. We can’t say too much, lest we ruin the surprise!

Are you good readers? What are you currently reading?

Anne: I am a terrible reader! As a book translator and editor, I do almost nothing but read all day and so I find it very hard to sit myself down with a book at the end of a long day. But I do want to, so I keep trying. Right now, I am simultaneously reading ‘Lessons in Chemistry’ by Bonnie Garmus, Johan Fretz’s ‘Met Vriendelijke Groet’, and ‘Wizard of the Crow’ by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – and have been for ages.

Becky: I like to keep a fiction book and a non-fiction book on the go at the same time. I’m currently reading Jonathan Franzen’s ‘Purity’ (I’m a huge fan) and ‘Black and White Styles in Conflict’ by Thomas Kochman.

|

Blog post by: Paula Arellano Geoffroy Website: paulaarellanogeoffroy.com LinkedIn: paula-arellano-geoffroy |

Written by: Claire Niven

Published: 23-09-2024

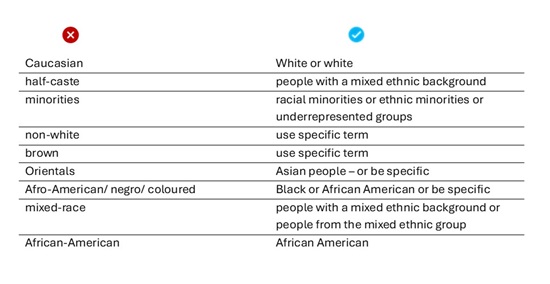

- Be precise when talking about identities.

- Replace harmful terms with more neutral language.

- Listen to how people describe themselves and if in doubt, ask.

- Keep learning!

|

Blog post by: Claire Niven Website: www.echt-english.nl LinkedIn: echt-english |

Published: 10-09-2024

On 6 July, I attended the SENSE Summer Social, which this year was held at the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, followed by lunch at Loetje Leiden. The event, organized by Becky Tomas, was a well-attended and enjoyable day exploring the multi-faceted gardens.

I was very excited to have an official tour of this historic garden, and to meet new colleagues. Though I joined SENSE several years ago, this was my first in-person event. I am a relatively new copy editor, and participating in a professional community where I can learn and grow is important to me.

On the rainy and windy Saturday morning, the sound of SENSE members and their partners greeting one another filled the glass house entrance hall of the Hortus botanicus. From the way people asked after each other’s families, it was clear that SENSE has facilitated many lasting friendships. This struck me particularly, as working for one’s self, as I do, is potentially isolating and lonely.

More than 40 people attended; I had never before been in the presence of so many language professionals at once. As a dedicated introvert, I found the noise and number of people to be a bit overwhelming. But my social anxiety was quickly put to rest by how welcoming and friendly people were. Throughout the day, multiple SENSE members approached me to introduce themselves and welcome me to the event and to the group.

Once everyone had arrived, we split into three groups and took guided tours of the gardens. The tour was very interesting and informative, and being in a smaller group allowed me to learn a little about some of the other members. I was impressed by the breadth of knowledge represented in our small group; many thought-provoking questions were asked of our guide, and some SENSE members were even able to provide additional information and context about the plants and the history of Leiden.

Once everyone had arrived, we split into three groups and took guided tours of the gardens. The tour was very interesting and informative, and being in a smaller group allowed me to learn a little about some of the other members. I was impressed by the breadth of knowledge represented in our small group; many thought-provoking questions were asked of our guide, and some SENSE members were even able to provide additional information and context about the plants and the history of Leiden.

The Hortus botanicus, our guide explained, was established by the University of Leiden in 1590, less than 50 years after the world’s first botanical garden at the University of Padua in Italy. The garden’s layout have understandably changed as the garden has grown and evolved over 400+ years, reflecting the history of the Netherlands and Europe.

It seemed appropriate that a society of language professionals, hailing from different countries and with different backgrounds, would meet there, in a place that has represented since its founding the Dutch engagement with the rest of the world.

A relatively recent effort, completed in 2009, has restored the original garden as it would have been in 1590 under the prefecture of botanist Carolus Clusius. The original collection, intended to benefit the university’s medical students, housed both medicinal plants and those plants gathered from abroad by the Dutch East India Company – including the infamous tulip.

As we walked through the somewhat wild reconstructed garden, a few SENSE members commented that many of the plants grown there also grow in their own gardens across the North Sea in the UK. Dutch-speakers and English-speakers shared the plants’ respective common names, often finding similarities.

My reminder of home came in the form of the swamp cypress (Taxodium distichum); though not particularly notable, the tree is native to the southern United States, where I lived for a year (from my native California) before I moved to the Netherlands.

As it was a particularly windy day, we spent the largest part of our time in the glass house with the tropical plant collections. Though we’d sadly missed the smelly bloom of the Amorphophallus gigas (native to Sumatra), we were impressed by carnivorous pitcher plants, a giant elephant ear (Colocasia gigantea from Thailand), and the soft pink bloom of a giant water lily (Victoria amazonica from the Amazon rainforest).

As it was a particularly windy day, we spent the largest part of our time in the glass house with the tropical plant collections. Though we’d sadly missed the smelly bloom of the Amorphophallus gigas (native to Sumatra), we were impressed by carnivorous pitcher plants, a giant elephant ear (Colocasia gigantea from Thailand), and the soft pink bloom of a giant water lily (Victoria amazonica from the Amazon rainforest).

As I looked around at the international group of SENSE members, I couldn't help but feel a kinship to the plants so lovingly cultivated and cared for by the botanists of the Hortus botanicus: we are most of us transplants ourselves, and have made the Netherlands our home and the source of our professional community.

The tour could have easily gone on all day, as we’d only viewed a fraction of the gardens. But as our bodies were tiring and our stomachs were hungry, I was happy to start the trek to Loetje Leiden, where three large banquet tables were waiting for us in a private room.

Over lunch, I had the opportunity to get to know my table mates as we chatted over cheese croquettes, a tasty goat cheese salad, and generous plates of sandwiches. The conversation was stimulating, ranging from the language profession to our personal life histories, to the best activities to do with children in the Netherlands.

Though I did not have the opportunity to visit with everyone, I was impressed by the obvious depth of knowledge of those SENSE members with whom I did visit. As a new editor, it was inspiring to meet so many who have not only made successful, longstanding careers in the language profession, but have also made the Netherlands their true home. I look forward to growing my own connections with this dynamic and welcoming group of people.

|

Blog post by: Rachel Porter Website: rachelporterediting.com Blog: rachelporterediting.com/blog LinkedIn: rachel-porter-editing |

Published: 27-08-2024

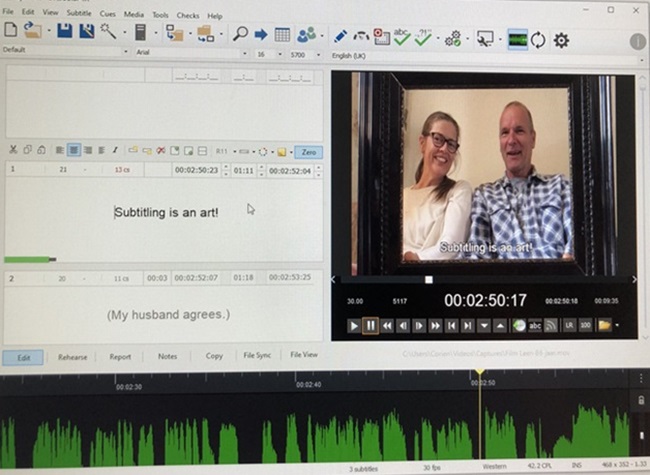

I made my very first subtitle in 1993 and I fell in love on the spot. Subtitle translation is such a wonderful mix of skills! After more than 30 years I still get a kick out of getting it exactly right. And that’s a lot more complicated than you might think…

I wrote my master’s thesis on subtitling, analysing the translation of humorous content in episodes of ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ and ‘The Young Ones’. But even so I had only the faintest grasp of the ins and outs of subtitling before I started working as a subtitle translator. So what are all these skills you need in order to be good at this? Allow me to share the four most important ones.

First of all, you need to be able to condense because subtitles must be short. If you translate everything that’s said in the video, either your whole screen will be covered in words or you’d have to make titles that flash by too fast for viewers to read them. Reading will always be a slower brain process than listening; it’s almost a law of physics. So you condense, and you learn to put in the essence of the meaning.

Condensing sometimes involves tough choices. Here’s an example. A detective arrives at a crime scene and is told by his sergeant: ‘63-year-old male victim, died of multiple stab wounds, time of death approximately 11 o’clock, SOCO will be here in 20 minutes. Coffee?’ That took eight seconds. You could make two four-second subtitles here. That would give you four lines of about 30 characters each. The software indicates how many you can put in to stay within the reading speed. That’s not enough to translate everything, so what do you leave out? You could leave out the coffee because it comes last and all the viewers will hear it clearly, but that might have an annoying effect. You’ll need space to explain what SOCO is. With luck the image will show something useful, perhaps the stab wounds, so you might skip those. You’ll have to find out if the age of the victim is relevant; if not, you might skip that. And so on. If the speech is slow, you’re lucky, but fast speech means lots of condensing without losing the essence in translation.

This need to condense, incidentally, is why I soon learnt not to tell people I’m a subtitler. I got tired of defending my work and explaining the reading speed thing. So at parties, or when meeting old acquaintances, I would avoid the subject of my profession to keep them from going off on the usual tangent: ‘Oh, TV subtitles are awful! They never translate what is said! Even I could do a better job!’ Sure, sure. One time this strategy bit me in the ass because I lied and said I was a pastry cook. Turns out, so was the person I was talking to.

A second skill you need as a subtitle translator – perhaps obviously – is an absolute mastery of the two languages you work with. Having an extensive vocabulary at your fingertips means you can pick the shortest word or phrase for your subtitle translation. You rebuild sentences, cut them into bits to accommodate reading speed, and do it fast because there’s always a deadline!

Third, being able to work with the software because subtitling is quite technical. Learning to work with the software takes time. One second of footage has 25 frames and your job is to time each subtitle to synchronize with the spoken word, down to the frame: 1/25th of a second. The software helps you pinpoint when your subtitle pops up and when it disappears. It also tells you when you put too many characters into a title (so viewers won’t have enough time to read it), or if the line is too long to fit the screen.

When you work for a range of clients, you need to be aware of their different styles. For example, some clients want three-frame intervals between subtitles so the eye will perceive the change. Other clients absolutely forbid subtitles staying on across a shot change. Some allow two speakers in one subtitle with a hyphen to separate them, some don’t. Things like that.

And the fourth skill, while you do all this, is remembering the underlying principle of subtitles: they should be like glasses. They help you watch a movie, but you shouldn’t be aware of them all the time. Subtitles should be unprovocative and so easy to read that you almost forget they’re there.

Studies show that subtitles are a terrific language-learning tool, especially for people whose native tongue is a minority language. In the Netherlands, TV subtitles are more widely read than newspapers. Vast quantities of video material become accessible to the deaf and hard of hearing thanks to subtitling.

Sadly, a lot of subtitle translators need other work on the side, or some other source of income (like rich parents or a partner with a good job) to make ends meet. This is not a well-paid profession. Most video content producers put subtitling way at the bottom of their budgets – often less than 1%. Most viewers will accept shoddy subtitles as a fact of life – they’ll complain, but not to the network or the studio. I was lucky enough to be in permanent employment with a media company for the first 13 years of my subtitling career, but most subtitle translators I know are freelancers. On top of all this, I suspect there will be plenty of AI software and apps in the very near future that will replace human subtitlers.

So there you have it! A fantastic profession, important even, but sadly undervalued. Long may it live.

|

Blog post by: Corinne McCarthy LinkedIn: corinne-mccarthy |