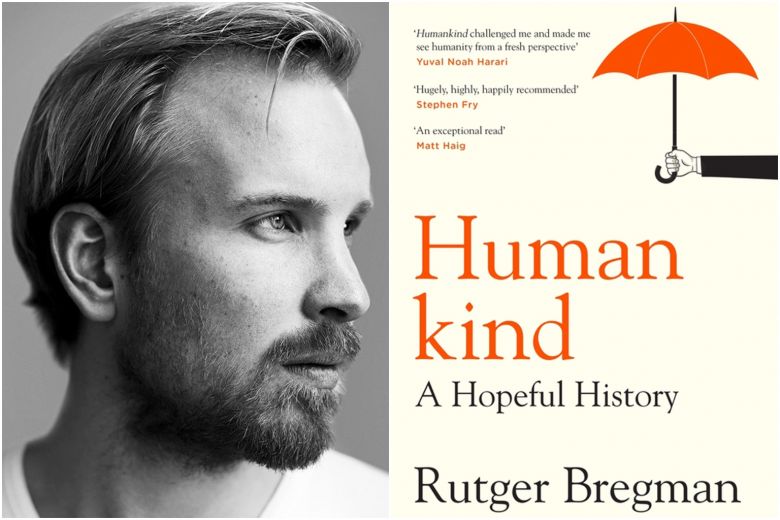

I wonder if, like me, you were on the waiting list to read De Meeste Mensen Deugen by Rutger Bregman last summer. I found myself surrounded by family members utterly absorbed in this book, a bestseller which suggests that human nature is kinder and more generous than we think. My name was way down on the waiting list for the book, but then someone suggested I read the English version. And that’s what I did.

Curious, as I always am, to see who the translators were, I was delighted to discover that one of them, Erica Moore, has been a member of SENSE since 2015. I decided to contact Erica to find out more about this challenging assignment. She was delighted to answer my questions, pointing out that authors are often inundated with calls for interviews and articles. Translators and editors? Not so much!

Erica, where are you from and what is your background?

I’m from Austin, Texas and came to Amsterdam for a year after uni on a Fulbright grant. I then stayed on for another year at the UvA, where I did Science and Technology Studies. At UT Austin, I majored in Plan II, an honours liberal arts program with classes in everything from English Lit. to Environmental History to Modern Physics. So I got a degree in a little bit of everything. Turns out that’s also the perfect foundation for being a translator. You’re keenly aware of how little you know, but you have a basis in a wide range of subjects, and solid training in critical thinking and writing. So you can dive deeper into any topic.

How did you meet Rutger Bregman and Elizabeth Manton?

I met Rutger when I joined De Correspondent back in 2015. And I sat across from him for the next few years at the old newsroom on the Amstel. I was hired to help them get set up to go international. I put together a team to translate pieces by the Dutch correspondents, edited the work of US writers like Sarah Kendzior and Bill McKibben (US environmental activist and founder of grassroots movement 350.org), and started an English newsletter to go out once a week and generate interest in the stories and the writers and the DC brand of journalism. I wore a number of hats at the startup, but my mission as head of translations was to ensure the voices of the different correspondents, and of the organization itself, would resonate with English speakers.

I met Elizabeth that same year, when I was scouting translators for an English edition of Rutger’s 2014 book Gratis geld voor iedereen. I handpicked a group of ten or so American translators – many of whom I found through SENSE – and asked them to take a crack at the first page or two. All ten samples were great, but one translator stood out because she showed a real feel for Rutger’s style from the get-go.

So Rutger, Elizabeth and I all met in a vast and empty pub in Utrecht, the city they both called home, and we got started. That was the beginning of Utopia for Realists. We’ve been a team ever since.

Could you tell us something about the translation process itself?

Logistics

After Elizabeth has completed her draft [translation] of a chapter, she’ll share it in a Google doc. It’s the best system we’ve found for collaborating on a text. Then I’ll go through and mark my edits and ask for changes, and Rutger and Elizabeth can respond whenever they get the chance. I ask them to leave all mark-up intact, so I can go through again and finalize everything, taking everyone’s input into account.

Sometimes we openly ponder what the best solution would be, with comments back and forth. Mostly, I’ll make a call or rewrite a line and that’s that. Sometimes, I’ll leave an issue open until the arc of the book becomes clearer to me, then I’ll go back and decide on that metaphor in chapter one, because it never comes up again. Or because it repeats in the epilogue. Rutger helps point out those sorts of links, too, since he knows the Dutch text through and through. I generally don’t read far ahead in the Dutch but look first to the English translation and how it works or where it lets us down, and try to fix that. I’ll pick up the Dutch book when I see a problem.

Style

At the start of a project, I write up a style guide – ostensibly for the translator and the editors and the copy editor, but mostly for myself. It’s my way of trying to get at the nuts and bolts of the author’s writing style. We can all add to it as we go. One of the things I put in there, for instance, was to keep in mind that Rutger is a skilled storyteller, with a great sense of timing and rhythm. It’s key we preserve that wherever we can.

Another point was to stay personable and breezy, close to natural spoken English. I’d edit a sentence like ‘It makes no difference whom you ask.’ to ‘Doesn’t matter who you ask.’ Or introductory clauses with commas, like ‘Consequently,…’ or ‘As a result,…’ get replaced by ‘And so…’. I found I could get rid of whole mouthfuls of clauses with that one: ‘The consequence of this inaction was that…’ becomes ‘And so…’. I also edited out more didactic phrases like ‘Let’s now imagine that…,’ replacing them with the friend-talking-to-friend version: ‘What if…’. These may seem like little tweaks, but the effect over 400 pages – if we got it right – is a text that sounds personal and draws you in close, like Rutger’s sharing a story with you, instead of aloof scene-setting and armchair observations.

For my fellow language nerds out there, here’s a couple more points from the guide:

Key: Avoid the subjunctive where possible. This book’s a grounded argument for what’s actually possible, not a string of lofty hypotheticals, e.g. ‘What if real democracy’s possible?’ not ‘What if democracy were truly possible?’ Rutger wants to take us beyond what we know and put us inside new, very real possibilities. That’s different from somehow transcending our current situation and gazing back down from a distance.

Key: Where possible, keep the personal perspective intact. Keep the people in the sentences, e.g. ‘Thanks to DNA testing, we now know…’ not ‘Recent DNA research has revealed…’. The edit sounds upbeat, accessible and includes the reader. We hear the person behind the writing. The old version sounds more distanced, stuffier, academic. (Nothing wrong with that, just not what we’re going for.) Writer and reader are absent.

Once everyone working on a manuscript is aware of that kind of thing, then odds are you won’t kill it. Take the subjunctive for instance, a deliberate choice on my part for Rutger. If you don’t make explicit your decision to avoid it, an earnest editor could correct out the author's style. Don’t get me wrong. That was not a problem here. Lots of fantastic people behind this book!

Having worked with Elizabeth on three book-length projects, and several shorter ones, I know that I don’t have to check her in a traditional sense. If she’s put a quote in, I know that she’s checked and double-checked it, and if there’s an original English version, that’s what she’s used. Because Elizabeth has done the heavy lifting, I can then focus on style and storytelling and argument. It’s a dream job – especially working with a fantastic author and a fabulous translator.